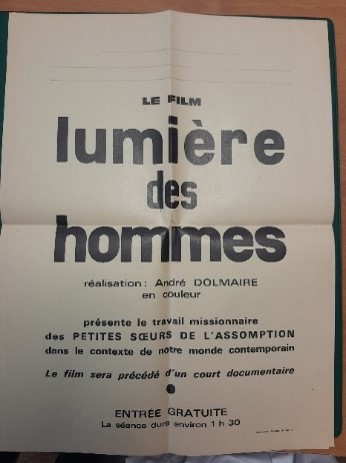

“The film Lumière des Hommes (The Light of Man”)

The large reels in these photos, contained in easy-to-carry cases, comprise a film produced in 1962 at the instigation of the congregation, entitled Lumière des Hommes (The Light of Man)..

The film’s narrative

It’s a 45-minute-long narrative film presenting the congregation’s mission and spirituality. It was made by professional film-makers, Mr. Dolmaire and Mr. Lorsay, but it is nonetheless the fruit of a truly collective effort led in particular by Sr Chantal de Soras (who, at the time, was known by her religious name, Sr Chantal du Christ), and Sr Humberte Mollière (Sr Marie-Humberte). The quality of this film is outstanding for its portrayal of the lives of the Little Sisters in the 1950s, particularly in their mission, and their perception of society, the world, and faith.

Origin of the work :

It’s hard to know with certainty from whom and where the first idea originated; it was probably from Sr. Chantal du Christ herself, who was then a member of the “Service général de la Propagande“, (“Propaganda Service”) an internal department of the Congregation created in 1947 (subsequently renamed the “Service général de diffusion et d’éditions” (General Distribution and Publishing Service) in 1958), and whose mission, according to its report to the 1958 General Chapter, was to “make the Congregation and its missionary activities known and loved, to arouse vocations and awaken apostolic concern in souls”.

One of the responsibilities of this service was publishing the magazine Dans nos sillons (In our furrows) (replaced in 1959 by Horizons Missionnaires (Missionary Horizons) and was directed at the time by Mother Marie Saint Jean de la Croix.

This same 1958 General Chapter “expressed the wish that a film be made soon, with the help of the regions, showing our missionary apostolate in different countries “(Vow n°28). Hence, it was only natural that this project should be entrusted to the “Service general de diffusion et d’éditions” (General Distribution and Publishing Service) particulary to Sr Chantal and Sr Marie-Humberte.

Creative process and cinematography

Sr Chantal wanted to avoid using a Parisian director both for financial reasons and because she feared she wouldn’t be free enough to make decisions about the film. The choice fell on Mr. Dolmaire and his company, based in Nancy, who had been recommended to her by a LSA friend and another congregation who had worked with him. Sr Chantal, on the other hand, lived in Grenelle. Understandably this geographical distance between them was not without difficulties at a time when even the telephone wasn’t as simple as it is today. But the many letters they exchanged constitute a valuable historical source and offer a definite advantage allowing us to see firsthand the creative process in operation, the message the LSAs wanted to get across, and also the technical choices that led to making the film we have today. Sr Chantal has kept them all – some 300 in all! The archives still hold the contract signed with the Dolmaire company and several stages of the screenplay. Added to these sources is a text written retrospectively by Sr Chantal herself (in 1992), entitled “History of the making of the film Lumière des Hommes, 1959-1964”. It is thus possible to retrace the entire creative process of this work.

At one point, for example, the question of the film’s title arose. Mr. Dolmaire had initially proposed the title “La Rivières aux Etoiles” (The Rivers of Stars), a title that didn’t appeal at all to Sister Chantal. In the end, they agreed to work around the idea of light. Sr Chantal suggested several titles and said she was inspired by Claudel… before proposing “Lumière des Hommes” (The Light of Man), referring to the text from Saint John (John I, 4-5) “In him was life, and that life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness., and the darkness has not overcome it.

In any case, these letters provided an opportunity on several occasions for Sr. Chantal to develop what she sought to express through this film.

For example, the feature film Au risque de se perdre (original title: The Nun’s Story, released in the USA in 1957 and in France in 1959), an American production directed by Zinnemann starring Audrey Hepburn. In this film, religious life is presented in a rather negative light, “one-sided and rather commercial”, according to Mr. Lorsay[1] (letter dated March 2, 1960). Sr. Chantal wrote to Mr. Dolmaire after viewing the film on the 13th of February 1960: “Regrettably, people will believe that we all lead a joyless life without fun or affection and that we force ourselves into tortuous obedience.” ” In her 1992 text, she also recounts the indignation she felt when she saw the film, and that on leaving the cinema with Sr. Marie-Humberte, she”was ashamed, on the way home, to feel burdened by everything that the film had thrust on the backs of the nuns in their convent!”

” In her 1992 text, she also recounts the indignation she felt when she saw the film, and that on leaving the cinema with Sr. Marie-Humberte, she

“was ashamed, on the way home, to feel burdened by everything that the film had thrust on the backs of the nuns in their convent!”

In short, the idea of Sr Chantal and Sr Humberte was to present religious life in a different light, to “show as much as possible the true face of this Life given to God.[1]

On the 7th of July 1959, while working on the screenplay, she wrote to M. Dolmaire: “I’ve come to hope that in our film, people would understand that God loves all of us, the poor men of the earth.”[2]

[1] Mr. Lorsay was Mr. Dolmaire’s right-hand man, who took over the direction of the film after Mr. Dolmaire’s death in February 1959

Difficulties and Completion

Apart from the choice of title, the screenplay had a challenging time getting off the ground. The distance made everything difficult, and Sr. Chantal rarely agreed with Mr. Dolmaire’s proposals; he had wanted to make such a film for a long time and therefore had his own ideas about what he wanted to do. On the other hand, Sr. Chantal’s perfectionist spirit became irritated and seemed to become discouraged by disappointing attempts and differences of opinion. “In one of her letters, she even exclaims, “There is so much anguish bottled up in this film?”

The anguish rising on Sr Chantal’s side can be felt through the impression that the film would never be made, and a tendency to regret the choices already made… You also have to try and imagine all the technical difficulties that arose. For example, it was decided to ask the regions to shoot mission scenes to give the film an international dimension. But the result was not always what Sr Chantal had hoped for, and there were also difficulties linked to the format, sending the reels, whether it should be made in black and white or colour… Most of the reels had to be shot a second time. Each scene was carefully thought out.

All these difficulties were compounded by Mr. Dolmaire’s illness, which made it increasingly difficult for him to travel to Paris (Sr. Chantal and Sr. Humberte themselves made the trip to Nancy several times). He finally died on the 10th of February 1962, three years after the first steps had been taken to make the film. He was replaced by his right-hand man, M. Lorsay, with whom things progressed more rapidly.

Shooting continued, and then came the long task of cutting and editing, as well as making “countless approaches to various organisations to obtain the authorization and the loan of passages from their films or documents that could be incorporated into our film to give it a broader missionary dimension and an openness to the contemporary world (for example, the SNCF, the Bibliothèque Nationale, Renault…)”[1]. A contract with SACEM (Society of Authors, Composers, and Publishers of Music) had to be drawn up for the copyright (for the music, for example) to be able to distribute the film afterwards.

Finally, the Nihil Obstat was given by Father Possidius Dauby on the 4th of March 1962, and the ministerial visa in October 1962. A great deal of work was also needed to finalise the English, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, and Brazilian versions.

[1] Quote from a text written by Sr Chantal de Soras in 1992, “History of the making of the film “Lumière des Hommes” 1959-1964″.

Screenings and reactions

The finished film was finally presented to the Mother General (Mother Ste Elisabeth) and 400 LSAs in Grenelle in September 1962 and was a resounding success. Many more screenings followed throughout France and the rest of the world

Here’s an example of a letter received after a screening, from a chaplain at a girls’ high school: “We showed your film to over two hundred girls, and our girls were won over…(…) It’s a film of high technical quality: it’s beautiful. Of high spiritual (and human, but they go together) quality; it’s great”.

Another excerpt from a letter:

“I didn’t find it tiresome, probably because there were no scenes of “pietism” and it skilfully avoids utilising facile sentimentality in situations that are sometimes quite sorrowful”.

Some comments are a little less enthusiastic:

“Attention is a little scattered. The concern to get the idea across makes the action less spontaneous, a little artificial…”.

Numerous screenings were subsequently scheduled, and the response was generally incredibly positive. In December 1962, the film was awarded third prize at the IVth International Meeting of the Christian Brotherhood in Belgium.

Several more screenings were held, but these were spaced out until the film was stopped altogether in 1969. Indeed, the film quickly became “outdated” at a time of momentous change in the Church. For example, from the time of filming, the question of the religious habit was under discussion, with a move towards simplification. Little by little, the nuns appearing in the film seemed to belong to an “old world”.

Nevertheless, this work is a powerful testimony to a whole era of the spiritual and concrete life of the congregation, and of religious life in general, around a time near to the Second Vatican Council.

Céline Hirsch

Archives Service of the Little Sisters of the Assumption

September 2023